Colorado Voices

Ken Burns on his new film, "Leonardo da Vinci"

Clip | 36m 7sVideo has Closed Captions

Ken Burns met with Rocky Mountain PBS to discuss his latest documentary on Leonardo da Vinci

Co-directed with Sarah Burns and David McMahon, Ken Burns' new documentary on Leonardo da Vinci is his first film on a non-American subject.

Colorado Voices

Ken Burns on his new film, "Leonardo da Vinci"

Clip | 36m 7sVideo has Closed Captions

Co-directed with Sarah Burns and David McMahon, Ken Burns' new documentary on Leonardo da Vinci is his first film on a non-American subject.

How to Watch Colorado Voices

Colorado Voices is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipKen, welcome back to Colorado.

Last time you were here, you were promoting the American Buffalo.

We were talking about answering this.

This question of who are we as Americans?

Now you're promoting a different film.

It's your first non-American subject.

How did you settle on Leonardo da Vinci and why now?

The folks most responsible for it are my co-directors.

My oldest daughter, Sarah Burns, and her husband, David McMahon.

And we've collaborated for years and years on a number of projects, including the Central Park Five and Jackie Robinson and Muhammad Ali.

I was didn't want to do it.

one of our biographers is, Walter Isaacson of of, our Benjamin Franklin had suggested this, and I just said, you know, I don't do non-American topics.

And I walked out of the dinner sort of a little bit miffed that he kept pushing and pushing and, I called up Sarah and Dave and they said, it can be a wonderful thing.

And so they've run with it.

And really, the film is very much a Florentine Films production.

And at the same time, it's got a new grammar and a new kind of relationship to music and a new kind of relationship to the visual way that we we talk about it.

And then at the end of the day, a good story is a good story is a good story.

And I love being over 70 and being able to, you know, this old dog got taught a new trick and I, I, I owe it entirely to Sarah and Dave and their sort of certainty and confidence and also the willingness to dive into a subject and, and to all of us together, the entire team figure out solutions to some really complicated problems.

You know, I'm working on a history of the American Revolution now, as I have for many, many years worked on the Buffalo.

Benjamin Franklin, also from the 18th century.

And there were lots of problems when there are no photographs and there's no newsreels.

And here's somebody that we're dealing with, the mid to late 15th century, in the very early 16th century.

That poses a lot of problems.

And and yet filmmaking is all about overcoming those problems.

So Leonardo becomes this just wonderful new friend that we've made in a new language and a new idiom, in a new kind of a way of approaching things.

It's been wonderful.

And Sarah and Dave are they are the authors of that interest.

Yeah.

You mentioned the films that some of the films you had worked on previously with, with Sarah and David.

Central Park five, Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali.

Very much rooted in social justice and racial justice.

Did this feel kind of like a a departure from that, working with them on this?

No, it's it's funny.

I know what you mean.

And you're absolutely right.

And this isn't that at all.

At the same time, a film.

It's all the same no matter what the subject is.

It's all a complicated thing about how you get up in the morning, put your pants on one leg at a time, and figure out how to solve complex issues of storytelling.

And that's what this is.

This happens to be a guy most of us use about 10% of our brain.

We're told he may be using 75, and I'm really interested in who that is.

And you know, to say genius is not doing it justice, to say polymath is not doing it justice, to say Renaissance man.

Which, of course, he literally is, is not doing it justice.

And something about meeting him and and the thing that I do to sort of invite folks into this story is you.

We know he's painted the most famous painting on Earth.

He's obviously one of the great painters.

But then you say, how many paintings did he have?

It's fewer than 20.

And how many of those are finished?

Fewer than ten.

Yeah.

And then you go, wait a second.

I have to know more.

And and that that animating curiosity has kept us going for years and years and years and Sarah and Dave and there are two small children to Italy for a year to do cinematography and research and writing and filming the intimacies of of of how we're going to overcome no photographs and then coming back and all of us struggling to figure out how to make it into a film.

Right.

I hear what you're saying.

That polymath doesn't even begin to describe it.

one of the folks in the documentary describes him as a supreme figure, and I feel like that was a good way of, you know, he's like, kind of like Shakespeare, da Vinci.

And then you almost run out of people, right?

You know, I, I made a film.

Oh my goodness.

It's almost 30 years ago on on Thomas Jefferson.

And despite all the flaws which we enumerated in the film, and there are many in there important, George Will commented in the film that you could argue that he, Jefferson, was the man of the last millennium, and to which you immediately think, yes, okay, but you start putting up arguments and then you wonder what are the alternatives?

And you come up with a Shakespeare.

You come up with maybe a Mozart or a Bach, you come up with Leonardo da Vinci, and, I'd have to put my money there.

I mean, I've got a bit of a of a as an American and working all my life on what, what Jefferson represents distilling a century of enlightenment which comes out of the Renaissance, thinking into the first government ever designed to have people run it and to be free.

And the pursuit of happiness was not to pursuit of objects in the marketplace of things, but was lifelong learning in a marketplace of ideas.

They all felt that that's what the capital H happiness was about, and I'm drawn to that is what public television is, is all about.

It's what my entire professional life has been about.

So I'm drawn to it.

And then you have Leonardo da Vinci, who is doing that his whole life on his own, and he doesn't have a telescope, and he doesn't have a microscope, and he doesn't have calculus, and he's figuring stuff out a century before Galileo and Newton and several centuries before this stuff that he did would people would confirm the results of his studies only after we had MRI eyes in the 70s could you say, oh, yes.

His design of the heart valve was exactly the way it works.

And and I want to know more and ever more because that's what he is.

He's he's about this monumental curiosity.

And every once in a while in our own lives, we touch on, we just have a moment somewhere where our observations are heightened and we see it more most often in nature.

And that was his great inspiration, too.

And then he just went further, where we have this almost rapturous moment.

He then asks, he has that moment, but then he asks a thousand questions and spends his entire life trying to ask not just those thousand questions, but the thousands of other questions that are constantly popping up in his head.

It's just so irresistible and makes you want to be a better person, a smarter person, a more observant person.

he we we do everything in our lives to categorize.

He's a scientist and a painter is when he's painting, he's a scientist.

When he's doing science, he's a painter.

He doesn't see the distinctions between them.

He's he's a human being, and he's closer to what our.

Purpose here on life is, which is unanswerable.

It's just a constantly sounded question.

And I think he he asked that question more firmly and more resolutely than anybody else I've ever come across, including the the, the Benjamin Franklin's, the John Muir's, the, the, the Martin Luther King's, the people that that I've come in contact with who seem to be really pushing the boundaries of the big questions, who am I?

Where did I come from?

What is my purpose in life?

Where am I going?

Yeah.

Speaking about the breadth of his work, I feel like visually, with this documentary, you communicated that kind of relationship between art and science and nature and man, in a really interesting way.

Can you tell me about the use of the split screen and how you kind of came up with that or settled on that?

Well, this is David and Sarah.

realizing that in a way, the limitations of the 15th and early 16th century could be the opposite of that or liberations.

And so if this guy is thinking about stuff in a way that feels so achingly contemporary now and dreaming up machines and things that he didn't think we're going to work in his lifetime, that we give him credit to, it's it's a, it demands new kinds of solutions.

So we have rocket ships in here.

We have some footage in here.

We have people, we have live footage of human beings moving their eyes and opening their mouths and turning their heads and smiling and crying and, and and that allowed us.

It liberated us and so.

Well, the the narrative is traditional, and we're using paintings and drawings where we might have had photographs and live cinematography, as we do in all films.

We're also, as his imagination takes off in any given, given arena, we're also saying, why not use two screens or four or 9 or 16?

And why can't you run it backwards and forwards?

And what about some animation and we how could we, in our own tiny, narrow minded way, honor the extent of his creative body in the sense that you get from commentator after commentator in the film, particularly Adam Gopnik, who's speaking English in our our film, Guillermo del Toro, the great filmmaker of Mexican speaking English in our film.

But there are Italian scholars and French scholars and others of just the sense that there's really been nobody like him that we can think of before.

Or if you if you do, then you have to bring up the names like Aristotle and Plato and Socrates, and they're only examples that you use past are Einstein and Newton.

And I'm really unaware of their great paintings, you know, I mean, that's, that's that's the kind of person we're dealing with who just looked at the universe and said, my obligation as Guillermo says, to, to sort of paraphrase him, is, is to interrogate the universe.

That's my gift.

Was it intimidating to make a film on a subject that just omnipresent, you know, it?

Maybe it should have been, but I liked our attitude all the way through.

Was our attempt to rise to the occasion.

And that's a that's an exhilarating aspect to it.

You can be cowed, but it's better to be exhilarated and want to be like Leo, you know?

I mean, you really want to aspire to something in your own lives that that touches that.

And so I think for everybody on the team and remember, it's a small nucleus, but it isn't just me for certain.

In this case, it's Sarah and Dave primarily, and me, but it's also editors, two spectacular editors and co-producers and and associate producers and sound editors and assistant editors and and it was it's a it's a really interesting family.

And then as we moved out to finish the film, the mixers and the sound cutters and all of that, so that by the time we had the finishing party, there was a kind of joy among everybody that we had participated in something really special.

It's not about the film, though.

We really are proud of it.

It's about the man.

It's about what he asks us to be, which is better, smarter, more curious, more insightful, more dedicated, more more hard working.

And so it it was the opposite of intimidation.

It was inspiration.

Yeah.

I found the film to be very moving.

You know, visually it's it's very interesting.

It's very different from your previous films.

but something that really stood out to me was the score.

Oh, I'm so glad you brought that up.

Yeah, yeah.

So this is I, I think I can say without insulting Sarah, it's David's thing.

We, we, we had and we're experimenting early in, editing with lots and lots and lots of different composers and things.

And it was working pretty well.

Dave really wanted to move all his eggs into one basket with the young, extraordinary composer Caroline Shaw, who also works not just instrumentally with musical instruments, but with two groups of of choral voices.

People, one called a roomful of teeth, you know, who are all about using the voice as an instrument of a different kind and his relationship, his enthusiasm for that was so infectious that you kind of had to just get out of the way.

And so, with the exception of a couple, what we call needle drops towards the end of the film, which are important narratively to just bring us into the present, it's all her.

And, it's interesting because she's recorded with various groups.

She's never put them all together.

And, and we're having next month in New York, a kind of concert in which you're showing clips from that film, but more importantly, we're having Carolyn and her musical groups and all the people coming together for the first time in public.

And and she's an extraordinary composer, and she is equal to the task was equal to the task and got it about Leonardo.

And I think it was Dave's.

It's almost safe to say, in the best sense of the word obsession, that the soundtrack is so compelling.

What was what was Dave and Sarah's research like?

I know they moved, to Florence for a time.

They moved for Florence for a year from July of 22 to July of 23.

They made several trips before and after.

so you're you you've got a multi-pronged effort that's going on there.

already a lot of research had been done, interviews had been done.

But you could conduct some interviews with scholars, mostly Europeans, British scholars, French scholars, Italian scholars, others Americans there.

but you're also doing live cinematography of the area around Tuscany and also, near Milan and up in the Italian Alps.

you're following the Arno River?

He's very much into water studies.

You're also there in a city which is dedicated to keeping alive the spirit of that 15th century bodega, the workshops where you'd have sculptors and painters all together, but also jewelry makers.

And so you have pigments being created and you have all sorts of stuff happening, and there's a visual stuff, and then there are people in Florence who have studied Leonardo.

He's left handed and he, like many left handers, are trying not to smudge, but he writes in a mirror script.

It's backwards.

Just think about all the thousands of thousands of pages he wrote.

Just the dedication to getting down his thoughts and his curiosities, and he and the results of his experiment.

But every time he's writing something down, it's in backward script, which means you can only read it in a mirror.

And how he's doing that, what kind of brain is able to do that?

And it's punctuated by all these exquisite drawings, sometimes of the human anatomy of flowers, of trees, of valleys.

You know, we think he's he did the first one of the first lands, if not the first landscape, drawing, in Western art, that he also did the first aerial map of a place so that he is so precious that he can see what only an airplane or a bird can see.

And he loves birds.

He's interested in flight.

He goes into the market and he buys all the birds, and he lets them go, you know, he lets them fly away.

So he's got a neighbor to, who's Amerigo Vespucci, who is going to be one of the European explorers of what they called the New World.

it's interesting that the first name of his neighbor is why we are the Americas, North and South and central.

And so maybe that's our, connection.

However, the name of my film company, which I started in 1975, is Florentine Films.

So now we might have finally come home.

You have achieved your destiny, achieved our destiny by finally doing a subject.

And it.

It's so wonderful.

It's also a beautiful, beautiful, language.

Italian.

It is also this period of the Renaissance.

Florence being the center of it, is a place where you want to be aware of, not just, Leonardo da Vinci, but the other people who are there, like Michelangelo and, brutal Laski and, Verrocchio and the other people who are part of this extraordinary outpouring of artistic talent, in that, in that period.

And so you're just rubbing up against the newest of the new and the best of the best.

Yeah.

The film begins one of the quotes from Da Vinci, and I'm paraphrasing, but he says a good painter must depict two things the person and then the intentions of their mind.

Right.

That's seems to me like something you do with your films.

Is it harder to do that when your subject is someone who we don't have interviews with or archival footage?

No, I don't think so.

It's very kind of you to say that it took me hearing Leonardo saying it to realize, boy, I wish that's what we were doing.

So that he said the first is easy.

You can represent the exterior of the person, but the intentions of the mind.

I think we have all of this writing.

We have a voice.

We have, Giancarlo Giannini, his son, who's middle age now, Adriano Giannini, who reads in English, Leonardo's writing.

And then it's punctuated by this sort of international united Nations of people, artists and filmmakers and theater directors and scholars and historians and biographers and scientists and surgeons who can help us understand him.

And so I think what we've tried to do in all the films is what I call what I describe trying to raise money for my first film called Brooklyn Bridge, which is an emotional archeology.

He's already doing that and doing it in such great dimensions.

Another way of answering your question, which is to the point, is to say, you know, one of the big jokes is his most famous painting is of a wife of a well-to-do silk merchant.

And that we we talk and we make jokes about her smile.

When you see this film.

You it's you won't ever joke about it again.

Or you can joke about it, but you will know why it is the way it is.

That is to say, it will be so transforming to get to that place where whatever's enigmatic and therefore uncomfortable for us, and therefore we have to make it funny or two mysterious, you'll realize that what he was able to touch was something so essential to this human project.

And, you know, just to be close to that for a few years, I consider that one of the luckiest aspects of my job.

Yeah.

Was it hard to just not?

I mean, you could make a documentary just on the Mona Lisa or just on The Last Supper.

Was it difficult to try to balance, like how much time you were spending with each of his works?

You know, I think it's for us.

You know, the English historian Thomas Carlyle said that history is biography.

It isn't entirely.

But even in our bigger works, the same many of the constituent building blocks of a big series are about human beings.

And a lot of our films are biographies.

You know, Sarah and Dave and I have done Jackie Robinson and Muhammad Ali and and.

Getting to know the arc of a life is a really important thing.

And so to me, I'm actually proud of the fact that the Last Supper scene or the Mona Lisa scene, Last Supper is the longest scene about anything in the film.

Is still short and even one of my favorite paintings, The Virgin of the rocks in the rocks, is is under three minutes and makes me cry every time I see it.

And it's narrated by one person, a Catholic priest, a monsignor who's art expert, Timothy Verdin, and, I don't know what to say.

It's just so powerful.

And so it was important for us to be able to gobble the whole of him up.

And he he, you know, it's interesting in biography of looking for lots of little tidbits and, you're not going to get much.

There's very little that we know about it.

We know some important things that are sort of in our tabloid sensibility.

All right, he's gay.

He's born out of wedlock.

We know this about that and this about that.

A few things, but not the way we know the ins and outs of of moments of Jackie Robinson's life or Muhammad Ali's life.

Not that they were covered because he's writing everything down, but because he is more interested in the questions he's asking of the world.

And so in a way, that's liberating.

So then you can say, yeah, sure, here, here are the things we know.

But isn't it better to be wondering about this first real painting on his own, The Annunciation or the Virgin in the rocks, or the Last Supper, or the Mona Lisa, whatever it might be, or the anatomy, or the drawings, or the inventions, or this or the also what's going on in Italy?

I mean, it's not a country, it's a set of states, and they're warring with each other and with outside forces.

And he's you know, Florence is ostensibly sort of quasi democratic or representative.

It isn't really.

And he goes to live in Milan, which is really ruled by a despot.

And, you know, it's just an interesting story in the midst of this thing that we call the Renaissance, and we just take the word apart for a second.

It just means a rebirth.

There had been a thousand years, at least, of just stilt vacation in what we call the Western world.

Nothing had really changed.

And then everything changed.

Everything changed in every dimension, way, shape and form.

Yeah.

One of the things I wanted to ask you about is in the film, one of the historians talks about how at the end of Davinci's life, there's this kind of disillusionment, and he's disappointed that he's not gonna be able to finish all these things.

I'm wondering how you might relate to that.

Well, you know what?

There's a couple of things.

He speaks about death with a kind of anger earlier on, and I kind of went, why, you know so much about life and death is such a part of life, and you're going to be dissecting cadavers, and you're understanding the beauty of a man who dies of natural causes at that age.

What's what's that unfulfilled thing for you?

And then that that I'm not sure how much that depression is really a part of it, whether it matters that much.

I know for myself that if I were given a thousand years to live, and I will not be given, I would not run out of topics in American history.

So there is that sense now, not just of urgency, but of greed.

You know, I'm working on more films now at 70 plus, at 71 years old than I have ever worked on at a time.

And I and it has to do with the fact that there's so many challenges and you want and every film is a million, literally a million problems.

You just don't see the word problem as pejorative.

You see it as the friction that you have to overcome in order for the plane to take off.

You have to see it for the runners.

I'll do another lap, you know, you have to see it for.

Yes.

I don't know how to tell it now, but maybe I'll figure out how to tell it before we like the picture.

Yeah, I want I was revisiting some of your previous work and some of the previous press you've done about your older films, and I want to float a comparison by you and, and see how it lands.

There's a part in the film where they're talking about Da Vinci kind of creating for the sake of creating, not finishing, but he's just really interested in the project.

And that reminded me of, the Frank Lloyd Wright documentary that you did, and you kind of talked about like, yeah, the roof might have leaked, it might have sagged here, but it was just about the creator of it all.

Do you think there's that's like a fair comparison?

Here's the thing.

And this is an intimate human thing.

Frank Lloyd Wright isn't a very nice person.

Yeah, I didn't like him.

Of all the biographies that we've done, he's the last guy I'd want to go out and have a beer with, or get in a car and do a cross-country trip with Leonardo.

Absolutely.

Because as the opening talking head after Guillermo and and Denardo, is is is his French biographer, Serge Bromley.

He says he was a work of art before he made any art that he himself was this incredible personality.

But you're absolutely right.

When you are at that level of pushing the limits of everything, you're asking too much of every single project.

Not in a bad way, but he just after a while, the limitations in that frame of that painting of that piece of poplar, that he's working on, it's just I'm done.

You know, it's not what the commission has suggested, but, you know, he said that to himself, you know, tell me, tell me, tell me, when is it ever finished?

And and there are a few spectacularly finished works of here's the Last Supper, included.

And so, yeah, I get it.

Frank Lloyd Wright is a towering genius and is, I think, still without equal among American architects.

But you're not drawn to him in the same way that Leonardo compels so much.

There's an arrogance about Wright and a kind of egomania about him, a selfishness that I hadn't yet.

I haven't yet felt with Leonardo.

Was there any I know some of the previous films you've done on people have very strong opinions about, just the subject matter, not necessarily the films, but I'm thinking about you know, the Vietnam War, the Civil War and the process of putting this film together.

Did you come across any sort of conflicting perspectives on Da Vinci or his work?

The problem is, and I wish Sarah and Dave could answer this a little bit better, because there's lots of conflicting stuff and a lot of it's in the weeds, you know, the new new stuff has come out that maybe his mother is Jewish and she came from Constantinople or whatever.

And and we're not going to say anything that the majority of scholars haven't yet.

Maybe they'll be irrefutable proof, and the film will be dated by the lack of our willingness to talk about Katerina in, in that way.

But she's there, and she is this sort of younger, lower class to compared to his father.

And notary.

And so they're not married and, and he's, he's, he's brought up in this little town which his father's from.

But it's, he works in Florence and it's Vinci.

And it's why when people say Da Vinci, you go, that's like me calling me of Walpole.

I live in Walpole, New Hampshire, you know.

But you would not say Kenneth Walpole, but you might, but you would never say of Walpole and know what you're talking about.

It was in if you look carefully in the film, it says, Pietro Leonardo say Pietro, meaning the son of Pietro, and that was his father.

This notary, and being born out of wedlock kept him out of university, which meant he couldn't have followed in his father's footsteps and become an accountant.

Which is really good for us.

Yeah, really, really good for us.

Yeah.

What is the one thing that you hope people take away from this film?

You know, it's it's sort of the question and it's one that we resolutely refuse to answer.

Not because it's not a good question, it's that we make a film.

And then when it's done, it's not ours anymore.

It's yours.

And then it's really my question to you, what do you take away from this?

What you know, what is it?

Because we don't want to to prescribe a certain area of inquiry on your own, nor do we wish to say this is exactly the way that you should approach it.

And so, you know, our films are multi-level.

I mean, people or get correspondence from people every week who are watching a film.

I've made Vietnam Civil War or something smaller like book, and they're learning something new on the fifth or the sixth of the 10th of the 15th watching.

And we're not putting those stuff in consciously.

We just have complex, layered narratives.

And so what you get is, is what you get.

I, I, I love this guy.

I wish that I, I, I wish my life was filled with as much energy and curiosity and observational skills as his.

It's not.

It hasn't been.

It will never be.

But it's okay to to want to be like him.

Yeah, yeah.

One of my takeaways was that I felt profoundly dumb in comparison to the.

And I think there's two ways to take it.

One is that kind of, you know, particularly in our angry culture today, it's sort of like, well then it must be the elites opposing the other.

The other way is to go, I'm not going to be that.

But I wish to know more.

And I do know something about tractors.

I do know something about crops and weather.

I do know something about how to work with my hands.

These are all things that, with the exception of tractors, although we probably anticipated them, something he was familiar with.

And so there's something that is non-elite about him.

Right.

And there's something in which he is insisting that we be elite, that we know more and ever more about something.

In fact, we live in a great country because there were so many extraordinary people from lower, as well as well-to-do backgrounds who brought a kind of intensity and courage and willingness to die for a cause that all of us are the beneficiaries of.

Still, nearly 250 years afterwards, I, you know, Leonardo, no matter how small he makes you feel, that's a good thing.

When we were working in the national parks, I came across a quote from a guy who was writing about Mount Denali in Alaska in the 19 teens.

It was then called, Mount McKinley, tallest mountain in North American continent.

And he said it reminds you of your atomic insignificance, right?

That's a good thing.

Yeah.

Right.

Because strangely, in the paradoxical ways, let's just say of nature, which would have been a great teacher to was a great teacher to Leonardo in the inscrutable and paradoxical ways of nature, experiencing your own insignificance makes you larger in spirits.

You, just as the egotist in our midst, is diminished by his or her self-regard.

Right?

That's why I can't put Frank Lloyd Wright and Leonardo in the same, you know, left place because one is diminished by that self-regard and the other is so humble in the face of this great handiwork, which in nature and in Colorado you have it in abundance.

You look out your window and you have the possibility to be awakened in that moment by something bigger and older than yourselves.

And yeah, I suppose it can make you feel small, but that also might be an inspiring aspect.

Yeah, I finished the film.

I saw Leonardo as someone so motivated by curiosity and just this hunger for knowing how things work.

Do you think in the our current kind of information age, where we have all the information we could possibly want in our phones, is it possible for another kind of Leonardo type to emerge, or is that, I think so, because, he inherits a classical tradition that's filling books, which is not dissimilar to what's in my phone.

A tsunami of information does come at it in the same way, in the same force, the same distractive stuff.

But it's there.

And he wants to know everything.

He really wants to know everything.

And yet everything is there.

I mean, you guys have mountains on your license plates, you know?

What do you you're saying go to the mountains.

John Muir knew this.

They're going to be the best teachers.

That's the most important thing that you have to do.

You know?

Well, Ken, is there anything else you'd like to add?

This has been great.

Thank you.

Thank you so much for your time.

It's good to see you again.

My pleasure.

Nice to see you.

When life gives you a house, move it.

Video has Closed Captions

Owning a home had always seemed impossible. Then a historic cabin became available. (1m 30s)

Meet the election judges behind La Plata County’s voting process

Video has Closed Captions

Selected community members in La Plata County began training as election judges. (4m 26s)

Sheldon Nuñez-Velarde: Master Potter of the Jicarilla Apache Nation

The Jicarilla Apache honor their longstanding relationship to the natural world. (5m 45s)

Rowena Mora: Master Basket Weaver of the Jicarilla Apache Nation

The Jicarilla Apache honor their longstanding relationship to the natural world. (4m 27s)

Plant Medicine of the Jicarilla Apache

The Jicarilla Apache honor their longstanding relationship to the natural world. (3m 27s)

The Jicarilla Apache Creation Story

Video has Closed Captions

The Jicarilla Apache honor their longstanding relationship to the natural world. (4m 57s)

The Jicarilla Apache honor their longstanding relationship to the natural world. (5m 37s)

Ducklings Told to Protect the Lake

The Jicarilla Apache honor their longstanding relationship to the natural world. (2m 35s)

Video has Closed Captions

Inside the high-stakes world of competitive pumpkin growing (4m 58s)

Temple Grandin analyzes undercover video taken inside Superior Farms slaughterhouse Denver

Video has Closed Captions

Undercover video taken inside Denver's Superior Farm plant with commentary from Temple Grandin (1m 54s)

The costuming family behind 60 years of handmade costumes in Colorado Springs

Video has Closed Captions

The Saunders family once operated one of the largest custom costume shops in Colorado Springs (4m 56s)

Voters to decide fate of Denver's only slaughterhouse

Video has Closed Captions

Superior Farms, the city’s only slaughterhouse, would be shut down if voters pass Ordinance 309. (8m 14s)

Keeping tradition alive with the CSU marching band

Video has Closed Captions

Inside the Colorado State University marching band. (2m 49s)

After 40 years, one of Colorado’s most challenging math competitions may be coming to a close

Video has Closed Captions

UCCS mathematics professor Dr. Alexander Soifer's Soifer Mathematical Olympiad turned 40 this year (5m 19s)

Behind the scenes at the Maurice Sendak exhibit

Video has Closed Captions

Behind the scenes preparing for Denver Art Museum’s Maurice Sendak “Wild Things” Exhibit (3m 37s)

Video has Closed Captions

The Kit Carson Café fills stomachs, job boards and the need for community gathering spaces (3m 5s)

Inside Colorado's newest high school sport: girls' flag football

Video has Closed Captions

Inside Colorado's newest high school sport: Girl's flag football (2m 44s)

Painting a mural from start to finish

Video has Closed Captions

Greeley painter, Alonzo Harrison, hits his stride in a new mural at WeldWalls festival. (2m 31s)

Video has Closed Captions

Southern Ute Vice Chairman Lorelei Cloud explains the importance and sacredness of water to all. (2m 9s)

Video has Closed Captions

Studying the ecological importance of ground squirrels at the Rocky Mountain Bio Lab. (4m 11s)

Video has Closed Captions

Over 1700 elementary to high school girls explore careers in transportation and construction (3m 8s)

New suburban opioid treatment clinics aim to address a less visible need outside Denver

Video has Closed Captions

Community Medical Services, an addiction treatment program, is opening six new suburban locations (2m 29s)

How Coloradans are working to overcome the political divide

Video has Closed Captions

Braver Angels uses cross partisan conversations to overcome political divides. (4m 8s)

Chile farmer and cofounder of the Pueblo Chile & Frijoles Festival Dr. Mike Bartolo

Video has Closed Captions

The retired CSU Fort Collins researcher has spent decades developing new types of chile peppers (3m 21s)

Colorado rural hospital relies on nurse midwives to provide quality care, keep costs down

Video has Closed Captions

Call the Midwife: Colorado rural hospital leans on nurse midwives for quality care, lower costs (4m 30s)

How a measure makes it onto Colorado's election ballot

Video has Closed Captions

Here's how an initiative goes from an idea to a ballot measure (4m 23s)

Water project advances Tribal sovereignty, lifts communities in Four Corners region

Video has Closed Captions

A look at how The Dolores Project changed lives in the Colorado Ute communities. (3m 31s)

The secret collection in Rangely that they don't want to keep under wraps

Video has Closed Captions

Everyone has a hometown, but not all have a car museum the size of a football field in them. (2m 38s)

For Colorado’s deaf high school volleyball players, the mindset is still the same

Video has Closed Captions

The over 65 year-old volleyball program for deaf students starts the high school season (4m 39s)

First-of-its-kind mandate requires in-person voting in Colorado jails

Video has Closed Captions

This election, every jail in Colorado will hold an in-person voting event for eligible voters. (3m 33s)

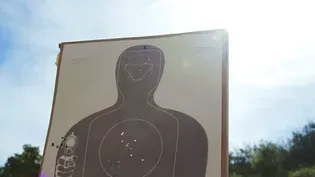

Why some Colorado schools have staff in firearms training

Video has Closed Captions

Schools, particularly in rural areas, consider training and arming school staff (5m 52s)

This Denver barbershop is staffed by formerly incarcerated barbers

Video has Closed Captions

R&R Head Labs hires formerly incarcerated barbers (2m 51s)

Video has Closed Captions

How poetry provided an outlet to Fort Collins Poet Laureate, Melissa Mitchell. (2m 42s)

Video has Closed Captions

Local newsrooms in Colorado are shrinking at alarming rates (4m 36s)

Ken Burns on his new film, "Leonardo da Vinci"

Video has Closed Captions

Ken Burns met with Rocky Mountain PBS to discuss his latest documentary on Leonardo da Vinci (36m 7s)

Election officials held a secret conference in Grand Junction amid security concerns

Video has Closed Captions

As conspiracy theories and lies about elections spread, the job of county clerk gets more stressful. (2m 43s)

Chef Safari brings a taste of Africa to Durango

Video has Closed Captions

Chef Safari brings African fusion cuisine to Durango, blending global flavors with cultural roots. (3m 14s)

Meet the sound artist who's exploring the symphony of nature at Rocky Mountain National Park

Video has Closed Captions

Meet the sound artist who's exploring the symphony of nature at Rocky Mountain National Park (3m 37s)

Water to water, dust to dust in the Arkansas Valley

Video has Closed Captions

Agriculturists unite with ag workers to sustain farms and farm towns in the Arkansas Valley (4m 4s)

Branching out: How one family’s science roots continue to spread

Video has Closed Captions

The Inouyes have been doing science for more than 50 years up in Gothic. (4m 57s)

The Colorado Youth Pipe Band is training Colorado’s next generation of bagpipers

Video has Closed Captions

The Colorado Youth Pipe Band is training Colorado’s next generation of bagpipers (3m 23s)

A Colorado LGBTQ couple's journey from foster care to adoption

Video has Closed Captions

Meet this LGBTQ+ family and their journey through the foster care system (5m 9s)

NASCAR or family car? Street racers hit the track

Video has Closed Captions

Can racing on designated tracks curb illegal street racing? Local police hope so. (3m 50s)

Video has Closed Captions

Matt Crane explains why election results in Colorado are reliable. (4m 43s)

Inside the tight-knit family of demolition derby

For decades, Greeley, Colorado has gathered to enjoy demolition derby. (2m 47s)

What’s the big deal about Manitou’s mineral springs?

Video has Closed Captions

Manitou’s namesake water feature has shaped the town geologically, economically and culturally (5m 13s)

Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Pride and Drag in Navajo Nation

Video has Closed Captions

On the last weekend of June, Navajo Nation celebrated Diné Pride at its capital. (4m 40s)

Video has Closed Captions

Incarcerated students find physical and spiritual healing in yoga program (5m 4s)

Baa Baa Buckaroos continue Mutton Bustin’ tradition at Pikes Peak or Bust Rodeo

Video has Closed Captions

The next generation of rodeo stars get their start on the backs of sheep (4m 7s)

Dancing with Parkinson’s, without limits

Video has Closed Captions

Boulder residents with Parkinson's disease find relieve and community in free dance class. (4m 1s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship